For a long time I’ve admired the tidytext package and its wonderful companion book Text Mining with R. After reading it I thought, “Why not undertake a project of Chinese text analysis?” I am deeply interested in Chinese philosophy but I decided to keep the analysis narrow by selecting just three works - The Analects, Zhuangzi, and the Mozi.

Following similar pace with Tidytext, I first download my data. Here I use my package ctextclassics and specifically, the function get_books(c(...)). But I want to point out the API limit is very low and I had to download my books between two different days. For information on ctextclassics, check out my previous post or type install_github("Jjohn987/ctextclassics")

library(tidyverse)

library(stringr)

library(ctextclassics)

library(tmcn)

library(tidytext)

library(topicmodels)

library(readr)

my_classics <- read_csv("~/Desktop/anything_data/content/post/my_classics.csv")With any text analysis, tokenizing the text and filtering out stop words is fundamental. Tidytext segments English quite naturally, considering words are easily separated by spaces. However, I’m not so sure how it performs with Chinese characters.

There are specific segementers for Chinese text - one main tool is jiebaR, which is also included in the tmcn package.

However, when comparing the two methods, I noticed that JiebaR segments text in a way most suitable for modern Chinese (Mostly 2 character words). Since I’m dealing with classical Chinese here, Tidytext’s one character segmentaions are more preferable.

tidytext_segmented <- my_classics %>%

unnest_tokens(word, word)For dealing with stopwords, JiebaR offers a useful stopword list, but obviously more should be added since we’re dealing with classical Chinese. Many of the words I added are amorphous grammar particles, but there’s other low value phrases amongst these works such as “子曰” (“The Master said”), “天下” (Tian Xia, a common but amorphous concept roughly meaning a country, realm, or the world), and more.

Let’s filter out those words and make 2 data frames - word frequencies for each book and each chapter.

stopwordsCN <- data.frame(word = c(tmcn::stopwordsCN(),

"子曰", "曰", "於", "則","吾", "子", "不", "無", "斯","與", "為", "必",

"使", "非","天下", "以為","上", "下", "人", "天", "不可", "謂", "是以",

"而不", "皆", "不亦", "乎", "之", "而", "者", "本", "與", "吾", "則",

"以", "其", "為", "不以", "不可", "也", "矣", "子", "由", "子曰", "曰",

"非其", "於", "不能", "如", "斯", "然", "君", "亦", "言", "聞", "今",

"君", "不知", "无"))

## Add a column that converts traditional Chinese to simplified Chinese

## Count words by book, then word frequency to account for different book lengths.

counts_by_book <- tidytext_segmented %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(simplified = tmcn::toTrad(word, rev = TRUE), pinyin = tmcn::toPinyin(word)) %>%

anti_join(stopwordsCN) %>%

count(book, word, pinyin, simplified) %>%

group_by(book) %>%

mutate(word_freq = `n`/sum(`n`)) %>%

arrange(-n) %>%

ungroup()## Warning: Column `word` joining character vector and factor, coercing into

## character vectorNow let’s do the familiar ritual of examining the top 10 words in each book (e.g, counts_by_book) and plot them.

book_top_words <- counts_by_book %>%

ungroup() %>%

group_by(book) %>%

top_n(10) %>%

ungroup()

##format the above dataframe for a pretty display with kable

formatted_words <- book_top_words %>%

group_by(book) %>%

transmute(word, simplified, n, word_freq, order = 1:n()) %>%

arrange(book, -word_freq) %>%

select(-order)

##Set format for kable

options(knitr.table.format = "html")

knitr::kable(formatted_words) %>%

kableExtra::kable_styling(font_size = 15, full_width = T) %>% kableExtra::row_spec(1:10, color = "white", background = "#232528") %>% kableExtra::row_spec(11:20, color = "white", background = "#6A656B") %>% kableExtra::row_spec(21:30, color = "white", background = "#454d4c") %>%

kableExtra::row_spec(0, bold = F, color = "black", background = "white") %>% kableExtra::scroll_box(width = "100%", height = "350px")| book | word | simplified | n | word_freq |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| analects | 問 | 问 | 110 | 0.0154321 |

| analects | 君子 | 君子 | 108 | 0.0151515 |

| analects | 仁 | 仁 | 76 | 0.0106622 |

| analects | 孔子 | 孔子 | 68 | 0.0095398 |

| analects | 行 | 行 | 57 | 0.0079966 |

| analects | 知 | 知 | 54 | 0.0075758 |

| analects | 路 | 路 | 52 | 0.0072952 |

| analects | 見 | 见 | 51 | 0.0071549 |

| analects | 民 | 民 | 45 | 0.0063131 |

| analects | 子貢 | 子贡 | 44 | 0.0061728 |

| mozi | 民 | 民 | 257 | 0.0068141 |

| mozi | 治 | 治 | 229 | 0.0060717 |

| mozi | 利 | 利 | 227 | 0.0060187 |

| mozi | 墨 | 墨 | 207 | 0.0054884 |

| mozi | 知 | 知 | 200 | 0.0053028 |

| mozi | 說 | 说 | 197 | 0.0052232 |

| mozi | 行 | 行 | 192 | 0.0050907 |

| mozi | 欲 | 欲 | 190 | 0.0050376 |

| mozi | 長 | 长 | 189 | 0.0050111 |

| mozi | 國 | 国 | 175 | 0.0046399 |

| zhuangzi | 夫 | 夫 | 313 | 0.0099356 |

| zhuangzi | 知 | 知 | 302 | 0.0095864 |

| zhuangzi | 見 | 见 | 222 | 0.0070469 |

| zhuangzi | 物 | 物 | 217 | 0.0068882 |

| zhuangzi | 大 | 大 | 204 | 0.0064756 |

| zhuangzi | 行 | 行 | 176 | 0.0055868 |

| zhuangzi | 邪 | 邪 | 165 | 0.0052376 |

| zhuangzi | 德 | 德 | 164 | 0.0052059 |

| zhuangzi | 道 | 道 | 164 | 0.0052059 |

| zhuangzi | 心 | 心 | 142 | 0.0045075 |

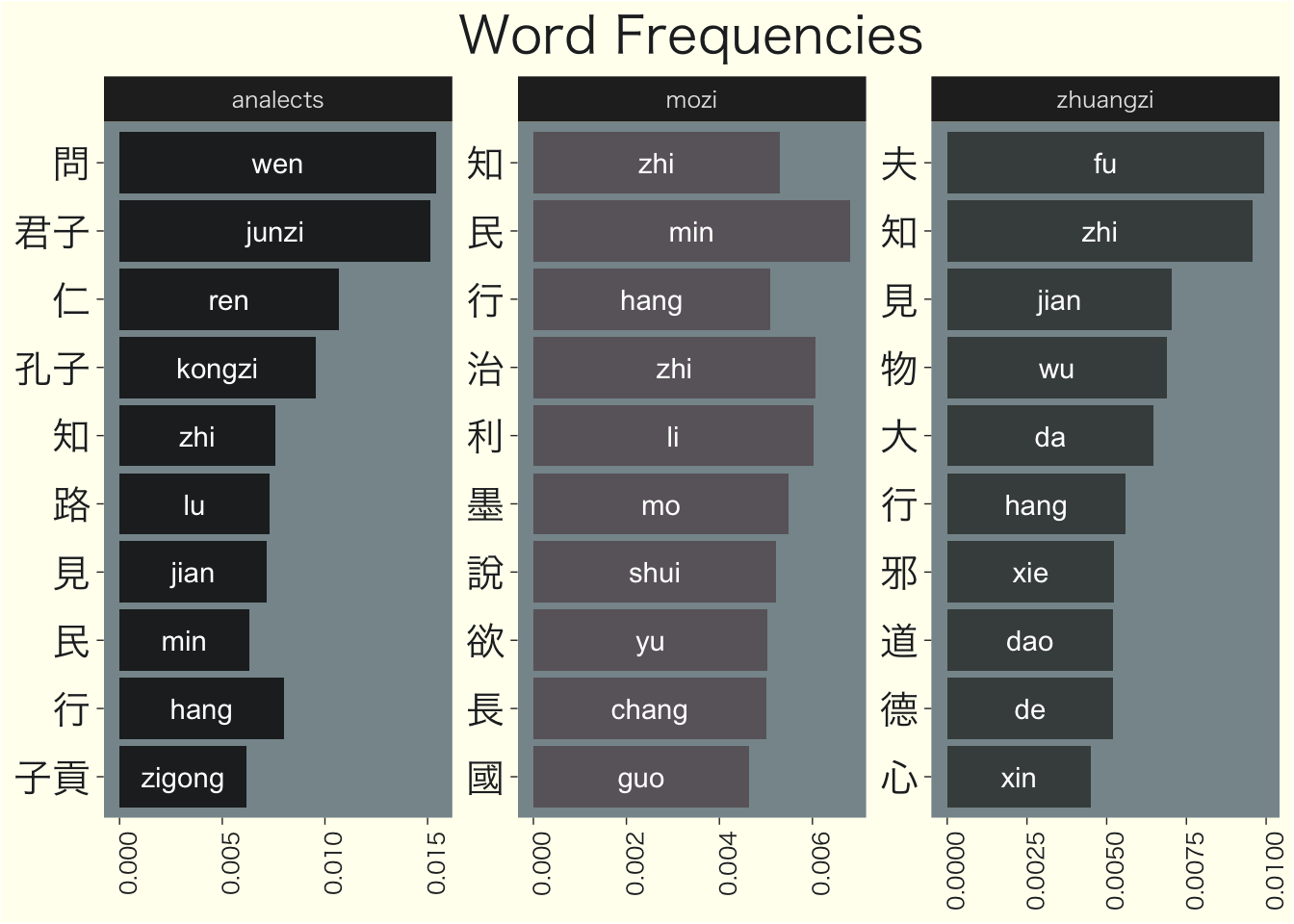

So far so good - these results are very intuitive. Of course, plotting them can accomplish this in even greater detail. Let’s plot the top 10 words and their respective frequencies from each of these texts, in calligraphy inspired colors!

ink_colors <- rev(c("ivory", "#454d4c", "#6A656B", "#232528"))

ggplot(book_top_words, aes(x = reorder(word, word_freq), y = word_freq, fill = book)) +

geom_col(show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_text(aes(label = pinyin), color = "white", position = position_stack(vjust = 0.5)) +

facet_wrap(~book, scales = "free", labeller = labeller(labels)) +

coord_flip() +

scale_fill_manual(values = ink_colors) +

theme_dark(base_family= "HiraKakuProN-W3") +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(color = "#232528", angle = 90)) +

theme(axis.text.y = element_text(color = "#232528", size = 15)) +

theme(panel.background = element_rect(fill = "#87969B"), plot.background = element_rect(fill = "ivory"), panel.grid.major = element_blank(), panel.grid.minor = element_blank()) +

labs(x = NULL, y = NULL) +

ggtitle("Word Frequencies") +

theme(plot.title = element_text(size = 20, color = "#232528", hjust = 0.5))

Summary

In this post, I…

- Used ctextclassics to download classic Chinese texts

- Split the text into character tokens of 1

- Filtered out common stop words

- Grouped the data by book and word, calculating total words and word frequencies

- Made a (calligraphy inspired) bar plot of the top 10 most frequent words in each text.

Conclusion

These word frequencies are very pleasing!

The Analects has prevalant usage of words such as “Benevolence” (仁), “Gentleman” (君子) and “Confucius” (孔子). (I capitalize these terms to show they are uniquely different from contemporary English equivalents.)

The Zhuangzi, a Taoist text, mentions cosmological concepts such as the Tao(道), morality (德), and evil(邪).

The Mozi seems to have terms that are mostly civic related, such as country (国), citizen (民) and govern(治).

These frequencies do a good job of capturing the context of the works - e.g., regarding the Analects, Benevolence and the Gentleman are often mentioned - one examplary sentence may be:

“君子而不仁者有矣夫。未有小人而仁者也.” My own (shorthand) translation:

Of Gentlemen, there are some who do not possess Benevolence; but of Villians, there is not a single one that possesses it.

Next Post

In my next post, I would like to either follow the same procedure but with bigrams, and/or apply LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation) to see whether chapters can be distinguished from one another.

Although frequent words are very different among texts, I’m not so sure that each book can be completely distinguished from others (There are many shared words - Dao isn’t solely mentioned in Taoist texts, and each text includes civic related concepts related to proper governance, plus, the Mozi is likely authored by different people!)

On that note, to be continued!